數位人文學

數位人文學 (英語:Digital humanities, DH),又称“数字人文”,是電腦運算或資訊科技與人文學的交叉學科[2][3] 。可被定義為以合作、跨學科與電腦運算等新方法來進行人文學的研究、教學、出版等學術工作[4] 。數位人文學將數位工具與方法帶進人文學中,並認為印刷書不再是知識生產與傳布的主要媒體。

藉由產出並使用新的應用與科技,數位人文學使得新型態的教學與研究成為可能。而同時又研究新科技如何衝擊文化遺產與數位文化 。因此,數位人文學的顯著特徵之一,是其對人文學與資訊科技雙方關係的深化:透過科技進行人文學研究,以及以人文學方法來研究科技對人的影響。

定義

數位人文學的定義正不斷地由學者與其他參與者界定中。由於其持續發展、改變的特性,特定的定義可能很快就會變得過時,或是成為對其潛力的限制[5] 。在《數位人文學的辯論》(英語:Debates in the Digital Humanities,2016年出版)一書的第二卷中提出定義此領域的困難:「除了數位典藏、量化分析、以及建立工具的計畫等曾經代表數位人文學的特徵外,數位人文學現在涵蓋了更廣泛的方法:大型圖庫的視覺化、文物的3D模型、數位原生的學位論文、標籤(hashtag)運動及其分析、擴增實境遊戲、活動自造者空間等等。在這個廣義的數位人文學中,很難清楚地定義數位人文工作必須包括什麼。」[6]

數位人文學自人文計算(humanities computing)發展而出,並於人文計算、社會計算(social computing)、媒體研究等相關。具體來說,數位人文學包括了從線上策展到透過主題模型(topic modeling)等方法進行的資料探勘。數位人文學使用數位化的資料與數位原生資料,結合傳統人文學(如歷史學、哲學、語言學、文學、藝術、考古學、音樂學、以及文化研究)與社會科學的方法論,[7] 以及電腦運算提供的工具(如超文本、超媒體、資料視覺化、資訊檢索、資訊探勘、統計學、文本探勘、數位製圖)與數位出版。另外,分支學科如軟體研究、平台研究,與批判程式碼研究也相繼出現。與數位人文學平行的學科包括新媒體研究、資訊科學、媒體寫作理論、遊戲研究、文化研究與文化組學。[8][9]

價值與方法

儘管數位人文學的計畫與倡議相當多元,其所反映的價值與方法有些共通之處[10] 。這些共通的價值與方法有助於瞭解這個難以定義的領域。[11]

價值

- 批判而理論的

- 反復而實驗的

- 合作而分散的

- Multimodal & Perfomative

- 開放而可進的

方法

- Enhanced Critical Curation

- Augmented Editions and Fluid Textuality

- Scale: The Law of Large Numbers

- Distant/Close, Macro/Micro, Surface/Depth

- Cultural Analytics, Aggregation, and Data-Mining

- Visualization and Data Design

- Locative Investigation and Thick Mapping

- The Animated Archive

- Distributed Knowledge Production and Performative Access

- Humanities Gaming

- Code, Software, and Platform Studies

- Database Documentaries

- Repurposable Content and Remix Culture

- Pervasive Infrastructure

- Ubiquitous Scholarship.[10]

為了維持開放、可近的價值,許多數位人文學計畫、期刊都是開放獲取或採用CC授權的,體現出此領域的開源標準與開放原始碼的支持[12]。開放獲取的設計是為了讓所有能上網的人都能免費觸及文章、並在一定的標準下分享。

數位人文學者透過數位方法回答現有的研究問題,或挑戰既有的理論範式,以產生新的問題和開拓新的方法。數位人文學的目標之一,是系統性地將電腦技術帶入人文學者的活動中[13]。如同今日的社會科學學者一般。儘管數位人文學顯著的往網絡的、多模型的知識型態發展,部分的數位人文學計畫則專注以不同於媒體研究、資訊科學、傳播學、以及社會學的的方式研究檔案與文本。數位人文學的另一目標,是創造超越文字的學科,這包括多媒体、元数据、動態環境的應用( 參見維吉尼亞大學的「山谷的陰影」計畫、南加州大學的「the Vectors Journal of Culture and Technology in a Dynamic Vernacular」計畫、以及哈佛大學的「Digital Pioneers」計畫[14]。

愈來愈多的數位人文學者透過資訊方法分析Google圖書等大型文化資料庫。這類的研究為2008年由數位人文學辦公室贊助的the Humanities High Performance Computing competition[15],以及2009年[16]、2011年[17]由美國The National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH)主辦、美國NSF[18]、英國JISC、加拿大SSHRC共同舉辦[19]的Digging Into Data challenge中獲得重視。除了書籍,舊版報紙也可以透過大數據方法分析[20][21] 。做為大數據革命的一部份,性別偏見、可讀性、內容相似性、讀者偏好、甚至心情都可透過文本探勘的方式來分析。[22][23][24][25][26][27]

數位人文學也與軟體的開發相關,如提供「數位原聲的知識生產、策展、互動的環境與工具[28] 」,在這脈絡下也將此領域稱為計算人文學。

工具

數位人文學者使用的工具相當多樣,這些工具可能存於移動裝置甚至虛擬實境實驗室中[30]。一些學者使用進階的程式語言與資料庫,而一些學者則使用較不複雜的工具。DiRT (Digital Research Tools Directory[31]) 提供了學者這些工具;TAPoR (Text Analysis Portal for Research[32]) 則為文本分析的入口。Voyant Tools[33] 是個線上的文本分析程式。Digital Humanities Tools[34] 則整理了許多免費的數位人文學研究工具。免費的線上出版平台如WordPress、Omeka等也是相當受歡迎的工具。

計畫

數位人文學計畫,相較於傳統的人文學工作,更傾於由一個團隊或一個實驗室進行。團隊成員可能包括教職員、研究生、大學生、資訊科技的技術人員、以及畫廊、圖書館、檔案館、博物館人員。作者的認證通常由多人共享,這點與傳統人文學通常只有單一作者的情形不同,而與自然科學的情形較為接近。

數以千計的數位人文學計畫中,從小規模、缺乏資金的計畫,到大規模、有持續資金援助的計畫都有。以下是一些例子:[35]

數位典藏

始於1998年的女性作家計畫,是個將前維多利亞時期女性作家著作數位化的長期計畫。1990年代開始進行的華特・惠特曼檔案[36] 則是建立了一個包括照片、音檔的超文本資料庫。2013年開始進行的埃米莉・狄更生檔案[37] 則藏有狄更生的高解析度手稿以及一個包括9000個出現在詩歌中的字詞的字典。

文本探勘、分析以及視覺化

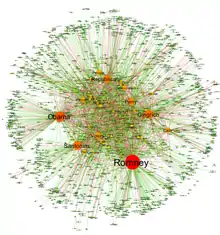

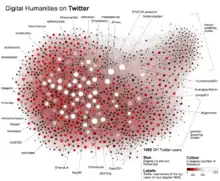

2004年開始的WordHoard 是個協助不熟悉科技的人文學者閱讀、分析的免費應用,收錄的文本包括古希臘經典、喬叟、莎士比亞、以及斯賓塞的著作。2008年開始的文人共和國以互動式地圖呈現啟蒙時代知識份子的社會網絡。 網絡分析與資料視覺化也用在呈現數位人文學這個領域本身,如呈現數位人文學者在社群媒體上的互動,或以資訊圖表呈現數位人文學學者、計畫相關資料等等。

線上出版

1995年開始的史丹佛哲學百科是個由哲學學者維護的百科全書。MLA Commons 提供了一個開放同儕審查的網站,內容為Digital Pedagogy in the Humanities: Concepts, Models, and Experiments (2016)的文物收藏。The Debates in the Digital Humanities 平台提供了同名書籍(2012年版與2016年版),讀者可以劃記、參與群眾外包的索引編輯等。

倡議

2010年開始的4Humanities是個由世界各地數個數位人文學者、教師所創設的網站,其目標在於透過提供工具與資源來提倡數位人文學。

2014年6月21日開始的Around DH in 80 Days,以每天介紹一個數位人文計畫的方式,以強調數位人文學的多樣性與全球性。

歷史

數位人文學的濫觴人文計算,可追溯至1940年代晚期耶穌會士Roberto Busa及其助手的研究成果[38][39]。Rboerto Busa與IBM合作,利用電腦建立了湯瑪斯・阿奎那著作的索引,稱為「Index Thornisticus」[4]。其他學者也開始使用大型主機來自動化檢索、排序、計數等工作[4]。接下來的數十年,考古學者、歷史學者、古典學者、文學研究者等等,也開始採用電腦運算。[40]

第一個專門期刊為1966年創刊的Computers and the Humanities,Association for Literary and Linguistic Computer (ALLC) 以及the Association for Computers and the Humanities (ACH)則分別在1977年與1978年成立。[4]

很快地,對數位文本標記規範的需求開始出現,首先發展的是Text Encoding Initiative (TEI) [4] 。1987年,第一個TEI計畫開始,隨後於1994年5月第一版的TEI Guidelines出版[39] 。TEI 形塑了電子文本的學術領域,並成為XML的濫觴。研究者也開始嘗試使用資料庫與超文本編輯,與傳統線性的印刷不同,超文本相互連結的點和線組成[4] 1990年代,美國各人文計算研究中心已經建置了眾多的數位文本、影像資料庫(如女性作家計畫、羅塞蒂檔案[41] 、威廉・布雷克檔案檔案等等)[42]這些資料庫表現了文字編碼在文學資料上應用的成熟與穩健[43] 。個人電腦與全球資訊網的發展使得數位人文學得以往設計發展。全球資訊網的多媒體特性使得數位人文學工作得以整合音檔、影片等資料。[4]

從「人文計算」到「數位人文學」的用詞轉變,始於John Unsworth、Susan Schreibman、和Ray Siemens所編的文選A Companion to Digital Humanities (2004),該書試圖強調此領域並非「僅僅是數位化」[44]。「數位人文學」的提出,創造了兩個重疊的領域,即「以現代人文學方法來研究數位對象」[44] ,以及「在資訊科技方法來研究傳統人文問題」[44] 。個人電腦系統的使用與對電腦媒體的研究被稱為「電腦運算轉向」。[45]

2006年 National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) 發起數位人文學倡議組織(2008年改名數位人文學辦公室),使得「數位人文學」一詞在美國被廣泛接受。[46]

數位人文學從上述的小眾議題發展為「大新聞[46],2009年於費城舉行的 MLA convention中,數位人文學者被認為是「最可見的貢獻提供者之一」[47] ,其領域則被視為「下一個件大事」。[48]

批判

Lauren F. Klein與Matthew K. Gold整理了對數位人文學的批評:其一、缺乏對種族、階級、性別與性慾特質等議題的關注;其二、相較於教學取向的計畫,更重視研究取向的計畫;其三、缺乏對政治的投入;其四、參與者缺乏多樣性;其五、著作權問題;其六、資源的過度集中。[49]

負面宣傳

Klein and Gold note that many appearances of the digital humanities in public media are often in a critical fashion. Armand Leroi, writing in the New York Times, discusses the contrast between the algorithmic analysis of themes in literary texts and the work of Harold Bloom, who qualitatively and phenomenologically analyzes the themes of literature over time. Leroi questions whether or not the digital humanities can provide a truly robust analysis of literature and social phenomenon or offer a novel alternative perspective on them. The literary theorist Stanley Fish claims that the digital humanities pursue a revolutionary agenda and thereby undermine the conventional standards of "pre-eminence, authority and disciplinary power."[50]However, digital humanities scholars note that “Digital Humanities is an extension of traditional knowledge skills and methods, not a replacement for them. Its distinctive contributions do not obliterate the insights of the past, but add and supplement the humanities’ long-standing commitment to scholarly interpretation, informed research, structured argument, and dialogue within communities of practice”.[4]

有些倡議以數位人文學做為眼下人文面臨的各種問題的解方:即資金缺乏、反覆的辯論、以及對理論與方法論的不重視[51] 。Adam Kirsch在New Republic中稱此為數位人文學「虛假的承諾」[52] 。 在其他的人文學部門以及社會科學部門面臨資金的缺乏與聲譽的下降之際,數位人文學所得的資金與聲譽則正在增加。數位人文學在討論中通常被視為革命性的替代方法,或只是舊瓶裝新酒。Kirsch認為數位人文學的參與者面臨的困難,在於推銷做得比研究多,這些工作只是在證實研究方法的能力,而非真的進行分析。就算是做了分析,也只是做些嘩眾取寵的內容而已。這類的批評也有其他學者提出,如Carl Staumshein即在Inside Higher Education中稱之為「數位人文學泡沫」[53];Straumshein則指控數位人文學是人文學「社團主義的重組」[54] 。一些人認為數位人文學與商業的結盟對人文學來說是個好的轉變,因為若能提高業界對人文學的重視,增加對人文學研究的資助[55] 。若不是「數位人文學」這個名字的包袱,這些計畫所獲得的資助是不公平的。[56]

「黑箱」

不清楚數位人文工具原理的學者對工具的過度信任,他們將資料放入這個「黑箱」裡頭,不清楚中間發生了什麼事,也不知道如何檢驗錯誤。洛杉磯加大資訊科學系教授Johanna Drucker稱此為「認識論的謬誤」,並認為這普遍出現在熱門的視覺化工具與科技,如網絡圖與主題模型工具對人文學工作來說仍過度粗糙[57]。

多樣性

另外也有對數位人文學參與者多樣性爭議的討論,Tara McPherson將數位人文學中種族多樣性的缺乏歸因於UNIX與電腦的模式[58] 。DHpoco.org上的一個開放的線程最近收集了關於數位人文學科種族問題的100多條評論,學者爭論了種族(及其他) 偏見對數位人文學者所使用的工具、文本的影響[59] 。McPherson認為需要理解即使分析的主題不是關於種族,也需要理解、理論化資訊技術對種族的影響。

Amy E. Earheart批評了在文本獲取計畫中,從使用簡單的HTML的網站,轉向使用TEI和視覺化,形成了數位人文學的新的「典範」。[60] 先前已經遺失或被排除的作品,現在可以網路上找到新家,但在傳統人文學中被邊緣化的作品,在網路上往往也被邊緣化。根據Earhart的說法,「我們做為數位人文學者, 有需要對目前我們正建立的這個典範展開檢驗,因為這個典範正傾向傳統文本,而排除了婦女、有色人種與GLBTQ社群。[60]

存取問題

Practitioners in digital humanities are also failing to meet the needs of users with disabilities. George H. Williams argues that universal design is imperative for practitioners to increase usability because "many of the otherwise most valuable digital resources are useless for people who are—for example—deaf or hard of hearing, as well as for people who are blind, have low vision, or have difficulty distinguishing particular colors." [61]In order to provide accessibility successfully, and productive universal design, it is important to understand why and how users with disabilities are using the digital resources while remembering that all users approach their informational needs differently.[61]

文化批判

數位人文學一直以來被批評不僅忽視傳統的人文學問題的系譜與歷史,也缺乏做為人文學基礎的文化批判。然而人文學是否必須與文化批判連結才是人文學仍是問題[62] 。科學視數位人文學為自非量化方法的進步。[63][64]

評價的困難

隨著此一領域逐漸成熟,學者們開始認識到既有學術同儕審查的標準模型,對數位人文學來說可能不適合,因為其計畫通常包括網站、資料庫等非印刷的內容。因此評價需要新舊混合的方法[4] 。對此問題的回應之一,是DHCommons Journal的設立,該期刊接受非傳統的投稿,特別是在計畫中程的數位人文學計畫,並提供較適合多媒體、跨學科、多階段性的數位人文學計畫的創新同儕審查方式。

對教學法缺乏關注

2012年版的 Debates in the Digital Humanities提出在教學法在數位人文學中是「被忽視的繼子」並加了一章討論數位人文學教學[6]。這個問題的成因之一,是贊助主要集中在能提供量化成果的研究而非難以評估的教學創[6] 。體認到此一領域教學的需要,Digital Humanities Pedagogy 提供了案例研究與在各領域如何教導數位人文學的策略。

組織

The Alliance of Digital Humanities Organizations (ADHO) is an umbrella organization that supports digital research and teaching as a consultative and advisory force for its constituent organizations. Its governance was approved in 2005 and it has overseen the annual Digital Humanities conference since 2006.[65]The current members of ADHO are:

- Australasian Association for Digital Humanities (aaDH)

- Association for Computers and the Humanities (ACH)

- Canadian Society for Digital Humanities / Société canadienne des humanités numériques (CSDH/SCHN)

- centerNet, an international network of digital humanities centers

- The European Association for Digital Humanities (EADH)

- Japanese Association for Digital Humanities (JADH)

- Humanistica, L'association francophone des humanités numériques/digitales (Humanistica)

- Taiwanese Association for Digital Humanities(TADH) 臺灣數位人文學會

ADHO funds a number of projects such as the Digital Humanities Quarterly journal and the Digital Scholarship in the Humanities (DSH) journal, supports the Text Encoding Initiative, and sponsors workshops and conferences, as well as funding small projects, awards, and bursaries.[66]

HASTAC (Humanities, Arts, Science, and Technology Alliance and Collaboratory) is a free and open access virtual, interdisciplinary community focused on changing teaching and learning through the sharing of news, tools, methods, and pedagogy, including digital humanities scholarship.[67]It is reputed to be the world's first and oldest academic social network.[67]

研究機構

- Department of Digital Humanities (King's College London, UK)

- Humanities Advanced Technology and Information Institute (University of Glasgow, Scotland)

- Sussex Humanities Lab (University of Sussex, UK)

- Digital Humanities Summer Institute (DHSI) (University of Victoria, Canada)

- The European Summer University in Digital Humanities (Leipzig University, Germany)

- Center for Digital Research in the Humanities (University of Nebraska-Lincoln, USA)

- Institute for Advanced Technology in the Humanities (University of Virginia, USA)

- Maryland Institute for Technology in the Humanities

- Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media (George Mason University, Virginia, USA)

- UCL Centre for Digital Humanities (University College London, UK)

- Center for Public History and Digital Humanities (Cleveland State University)

- Scholars' Lab (University of Virginia)

- Centre for Digital Humanities Research (Australian National University)

- Research Center for Digital Humanities (國立臺灣大學[National Taiwan University])

研討會

- Digital Humanities conference

- THATCamp

- Text Encoding Initiatve (TEI) conference

- Digital Archives and Digital Humanities (DADH from NTU & TADH, Taiwan, 2017201820192020, etc.)

期刊

- Digital Humanities Quarterly (DHQ)

- Digital Scholarship in the Humanities (DSH) (formerly Literary and Linguistic Computing)

- Digital Studies / Le champ numérique (DS/CN)

- Digital Literary Studies

- Journal of Interactive Technology and Pedagogy

- Journal of the Text Encoding Initiative

- DHCommons

- Kairos

- Journal of Digital Humanities (JDH)

- Journal of Digital and Media Literacy

- Digital Medievalist

- Southern Spaces

- Humanist discussion group via listserv

- Digital Archives and Digital Humanities《數位典藏與數位人文》

延伸閱讀

入門指南

- Intro to Digital Humanities by UCLA Center for Digital Humanities

- CUNY Digital Humanities Resource Guide by CUNY Digital Humanities Initiative

- DH Toychest: Guides and Introductions curated by DH scholar Alan Liu

- How did they make that? by DH scholar Miriam Posner

- The Digital Humanities: A Primer for Students and Scholars (2015)

- Digital Humanities in Practice (2012)

參見

- League of Nations archives, United Nations Office in Geneva.

- Drucker, Johanna. . UCLA Center for Digital Humanities. September 2013 [December 26, 2016]. (原始内容存档于2014-09-29).

- Terras, Melissa. (PDF). UCL Centre for Digital Humanities. December 2011 [December 26, 2016]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2012-01-31).

- Burdick, Anne; Drucker, Johanna; Lunenfeld, Peter; Presner, Todd; Schnapp, Jeffrey. (PDF). Open Access eBook: MIT Press. November 2012 [2017-01-17]. ISBN 9780262312097. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于2016-10-26).

- Warwick, Claire; Terras, Melissa; Nyhan, Julianne. . Facet Publishing. 2012-10-09. ISBN 9781856047661 (英语).

- . dhdebates.gc.cuny.edu. [2016-12-29]. (原始内容存档于2019-05-12).

- . University of Cambridge. [27 December 2012].

- Roth, S. (2014), "Fashionable functions.

- Liu, C.-L., G. Jin, Q. Liu, W.-Y. Chiu, and Y.-S. Yu. (2011) "Some chances and challenges in applying language technologies to historical studies in Chinese", International Journal of Computational Linguistics and Chinese Language Processing, 16(1-2):27‒46. (http://arxiv.org/abs/1210.5898)

- Honn, Josh. . Northwestern University Library. [19 September 2015]. (原始内容存档于2015年9月19日).

- Find accessible, brief descriptions of each at A Guide to Digital Humanities archived site.

- Bradley, John. . Marilyn Deegan and Willard McCarty (eds.) (编). . Farnham and Burlington: Ashgate. 2012: 11–26 [14]. ISBN 9781409410683.

- Opportunities/tabid/57/Default.aspx 请检查

|url=值 (帮助). National Endowment for the Humanities, Office of Digital Humanities Grant Opportunities. [25 January 2012]. - Digital Pioneers projects at Harvard

- Bobley, Brett. . National Endowment for the Humanities. December 1, 2008 [May 1, 2012]. (原始内容存档于2012-09-26).

- . Digging into Data. 2009 [May 1, 2012]. (原始内容存档于2012年5月17日).

- . National Endowment for the Humanities. January 3, 2012 [May 1, 2012].

- Cohen, Patricia. . The New York Times (New York). 2010-11-16 [2012-06-07]. ISSN 0362-4331.

- Williford, Christa; Henry, Charles. . Council on Library and Information Resources. June 2012. ISBN 978-1-932326-40-6.

- Dzogang, Fabon; Lansdall-Welfare, Thomas; Team, FindMyPast Newspaper; Cristianini, Nello. . PLOS ONE. 2016-11-08, 11 (11): e0165736. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 5100883. PMID 27824911. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0165736.

- Seasonal Fluctuations in Collective Mood Revealed by Wikipedia Searches and Twitter Posts F Dzogang, T Lansdall-Welfare, N Cristianini - 2016 IEEE International Conference on Data Mining, Workshop on Data Mining in Human Activity Analysis

- Flaounas, I.; Turchi, M.; Ali, O.; Fyson, N.; Bie, T. De; Mosdell, N.; Lewis, J.; Cristianini, N. . PLoS ONE. 2010, 5 (12): e14243. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0014243.

- Lampos, V; Cristianini, N. . ACM Transactions on Intelligent Systems and Technology (TIST): 72. doi:10.1145/2337542.2337557.

- NOAM: news outlets analysis and monitoring system; I Flaounas, O Ali, M Turchi, T Snowsill, F Nicart, T De Bie, N Cristianini Proc. of the 2011 ACM SIGMOD international conference on Management of data

- Automatic discovery of patterns in media content, N Cristianini, Combinatorial Pattern Matching, 2-13, 2011

- Lansdall-Welfare, Thomas; Sudhahar, Saatviga; Thompson, James; Lewis, Justin; Team, FindMyPast Newspaper; Cristianini, Nello. . Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2017-01-09: 201606380. ISSN 0027-8424. PMID 28069962. doi:10.1073/pnas.1606380114 (英语).

- Bol, P. K., C.-L. Liu, and H. Wang. (2015) "Mining and discovering biographical information in Difangzhi with a language-model-based approach", Proceedings of the 2015 International Conference on Digital Humanities. (http://arxiv.org/abs/1504.02148)

- Presner, Todd. . Connexions. 2010 [2012-06-09].

- Automated analysis of the US presidential elections using Big Data and network analysis; S Sudhahar, GA Veltri, N Cristianini; Big Data & Society 2 (1), 1-28, 2015

- Gardiner, Eileen and Ronald G. Musto. (2015).

- . [2017-01-17]. (原始内容存档于2019-04-24).

- . [2017-01-17]. (原始内容存档于2017-09-29).

- . [2017-01-17]. (原始内容存档于2018-02-24).

- Digital Humanities Tools website

- See CUNY Academic Commons Wiki Archive for more.

- Walt Whitman Archive website

- . www.hup.harvard.edu. [2016-12-26].

- Svensson, Patrik. . Digital Humanities Quarterly. 2009, 3 (3) [2012-05-30]. ISSN 1938-4122.

- Hockney, Susan. . Susan Schreibman, Ray Siemens, John Unsworth (eds.) (编). . Blackwell Companions to Literature and Culture. Oxford: Blackwell. 2004. ISBN 1405103213.

- Feeney, Mary & Ross, Seamus. . Historical Social Research. 1994, 19 (1 (69)): 3–59. JSTOR 20755828.

- Jerome J. McGann (编), , Institute for Advanced Technology in the Humanities, University of Virginia, [2012-06-16]

- Morris Eaves, Robert Essick, and Joseph Viscomi (编), , [2012-06-16]

- Liu, Alan. . Critical Inquiry. 2004, 31 (1): 49–84. ISSN 0093-1896. JSTOR 10.1086/427302. doi:10.1086/427302.

- Fitzpatrick, Kathleen. . The Chronicle of Higher Education. 2011-05-08 [2011-07-10]. (原始内容存档于2011-08-28).

- Berry, David. . Culture Machine. 2011-06-01 [2012-01-31]. (原始内容存档于2012-01-01).

- Kirschenbaum, Matthew G. (PDF). ADE Bulletin (150). 2010.

- Howard, Jennifer. . The Chronicle of Higher Education. 2009-12-31 [2012-05-31]. ISSN 0009-5982. (原始内容存档于2012-03-08).

- Pannapacker, William. (The Chronicle of Higher Education). Brainstorm. 2009-12-28 [2012-05-30]. (原始内容存档于2012-05-14).

- . [2017-01-17]. (原始内容存档于2019-04-21).

- Fish, Stanley. . The New York Times (New York). 2012-01-09 [2012-05-30].

- Leroi, Armand. . The New York Times Online. The New York Times. [14 May 2016].

- Kirsch, Adam. . The New Republic. The New Republic. [14 May 2016].

- Straumshein, Carl. . Inside Higher Education. [14 May 2016].

- Straumshein, Carl. . Inside Higher Education. Inside Higher Education. [14 May 2016].

- Carlson, Tracy. . The Boston Globe. [14 May 2016].

- Pannapacker, William. . Chronicle of Higher Education. [14 May 2016].

- . Vimeo. [2016-01-25].

- .

- . (原始内容存档于2013-12-03).

- http://dhdebates.gc.cuny.edu/debates/text/16

- http://dhdebates.gc.cuny.edu/debates/text/44

- Liu, Alan. . UCSB. [14 May 2016].

- . Nature. Nature. [14 May 2016].

- Kirschenbaum, Matthew. (PDF). Wordpress. Matthew Kirschenbaum. [14 May 2016].

- . adho.org. [2016-12-26]. (原始内容存档于2017-02-06).

- Vanhoutte, Edward. . Literary and Linguistic Computing. 2011-04-01, 26 (1): 3–4 [2011-07-11]. doi:10.1093/llc/fqr002.

- . HASTAC. [2016-12-26].

外部連結

- What is digital humanities? 页面存档备份,存于 - a critical project highlighting the diversity of DH definitions

- The Alliance of Digital Humanities Organizations - the main international alliance of DH programs

- CenterNet 页面存档备份,存于 - Mapping of DH centers