约瑟夫·康拉德

约瑟夫·康拉德(Joseph Conrad,1857年12月3日-1924年8月3日),原名約瑟夫·泰奧多爾·康拉德·納文奇·科热日尼奥夫斯基(Józef Teodor Konrad Nałęcz Korzeniowski, 波蘭語:[ˈjuzɛf tɛˈɔdɔr ˈkɔnrat kɔʐɛˈɲɔfskʲi](![]() 听))是一位波兰裔英国小说家[1][note 1],被认为是用英语写作的最伟大的小说家之一[2]。

听))是一位波兰裔英国小说家[1][note 1],被认为是用英语写作的最伟大的小说家之一[2]。

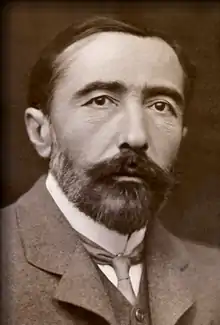

| 约瑟夫·康拉德 | |

|---|---|

1904年 乔治·查尔斯·贝雷斯福德 | |

| 出生 | 约瑟夫·泰奧多尔·康拉德·纳文奇·科热日尼奥夫斯基 1857年12月3日 俄羅斯帝國基輔州別爾基切夫 |

| 逝世 | 1924年8月3日(66歲) 英格兰肯特郡Bishopsbourne |

| 墓地 | 坎特伯雷公墓 |

| 職業 | 小说家 |

| 國籍 | 波兰 |

| 公民權 | 英国 |

| 創作時期 | 1895–1923: 现代主义 |

| 體裁 | 小说 |

| 代表作 | 《水仙号上的黑水手》(1897) 《黑暗之心》(1899年) 《吉姆爷》(1900年) 《台风》(1902) 《诺斯特罗莫》(1904) 《间谍》(1907) 《在西方的目光下》(1911) |

| 配偶 | 杰西·乔治 |

| 兒女 | 2 |

| 簽名 |  |

雙親皆死於政治迫害。他於1874年赴法國當上水手,1878年加入英國商船服務,並於1886年歸化英國籍。康拉德乃英國文學界裡耐人尋味的異客。他周遊世界近20年,37歲(1894年)才改行成為作家;在寫第一本小說前他僅自學了10多年的英文。康拉德的作品深刻反映新舊世紀交替對人性的衝擊。面對文化與人性的衝突,他並沒有提供答案,而是如同哲學家提供思索答案的過程。

虽然他直到二十多岁才流利地说英语,却是一位散文设计大师,把非英语的感性带入了英语文学[note 2]。康拉德写的小说,许多都是航海题材,描绘人类精神在冷漠的,难以理解的宇宙之中的考验。[note 3] 。

康拉德被认为是早期现代主义的先驅[note 4] ,尽管他的作品包含19世纪现实主义元素[3]。他的叙事风格和反英雄人物,[4]影响了许多作家,许多电影都改编自,或灵感来自他的作品。许多作家和评论家评论说,康拉德的小说作品,主要写于20世纪头20年,似乎预示后来的世界事件。[5][6]

康拉德写作时恰逢在大英帝国处于巅峰时期,又借鉴了家乡波兰的民族经历,以及他自己在法国和英国商船的经历[7][8][note 5],创作的小说反映欧洲主导的世界的各方面—包括帝国主义和殖民主义,并深刻地探索人类的心理.[9]。

他是少數以非母語寫作而成名的作家之一,被譽為現代主義的先驅。年輕時當海員,中年才改行寫作。一生共写作13部长篇小说和28部短篇小说,主要作品包括《黑暗的心》(1899年)、《吉姆爷》(1900年)、《间谍》(1907年)等。

生平

早年

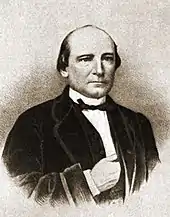

1857年12月3日,康拉德生於烏克蘭的別爾基切夫,当时属于俄羅斯帝國的一部分,此前曾经是波兰王国王冠领地的一部分[10] 。康拉德是作家、翻译家、政治活动家阿波罗·科尔泽尼诺夫斯基和埃瓦·博布罗夫斯卡的唯一的孩子。他的名字約瑟夫·泰奧多爾·康拉德·科热日尼奥夫斯基,分别来自于外祖父約瑟夫、祖父泰奧多爾、以及亚当·密茨凯维奇的《先人祭》(Dziady)和《康拉德·瓦伦罗德》(Konrad Wallenrod)两首诗歌里的英雄(都命名为"康拉德")。他的家人称他为""康拉德",而不是“约瑟夫”[note 6]

虽然周边地区的绝大多数居民是乌克兰人,而別爾基切夫城里的绝大多数居民都是犹太人,但几乎所有的乡村都归波兰什拉赫塔贵族所有,康拉德的家族属于其中的納文奇支系。[11]波兰文学,特别是爱国文学,受到当地波兰人的高度重视[12]:1。

科热日尼奥夫斯基家族在恢复波兰独立的努力中发挥了重要作用。康拉德的祖父特奥多尔曾参加拿破仑的俄法战争,效力于约泽夫·波尼亚托夫斯基亲王麾下,又在1830年十一月起义中,组建了自己的骑兵中队。[13] 康拉德热切爱国的父亲阿波罗属于"红色"政治派别,其目标是恢复分治前的波兰边界,但也主张土地改革和废除农奴制。康拉德后来拒绝追随阿波罗的脚步,以及他选择流亡而不是抵抗,是康拉德终生内疚的根源。[14][note 7]

由于父亲试图务农和进行政治活动,这个家庭一再搬家。1861年5月,他们搬到华沙,阿波罗加入了反抗俄罗斯帝国的抵抗活动。这导致他被监禁在华沙城堡[note 8]的十号楼[note 9]。康拉德写道:“这个城堡的庭院—这是我们国家的特征—我的童年记忆开始了。”[15]:17–19 1862年5月9日,阿波罗一家被流放到莫斯科以北500公里的沃洛格达,那里以气候恶劣著称[15]:19–20。1863年1月,阿波罗获得减刑,全家被送到乌克兰东北部的切尔尼戈夫,那里的条件好多了。然而,1865年4月18日,埃瓦死于肺结核[15]:19–25。

父亲阿波罗尽了最大的努力来教育康拉德。他的早期阅读带给他的两个元素,后来主宰了他的一生:维克多·雨果的《海上劳工》鼓励他将青春贡献给这个活动领域;而 莎士比亚把他带上英国文学的轨道。最重要的是,他阅读了波兰浪漫主义诗歌。半个世纪后,他解释说:“我作品中的波兰性,来自密茨凯维奇和斯沃瓦茨基。我父亲为我大声朗读密茨凯维奇的《塔德伍施先生》,让我大声朗读。.... 我过去更喜欢密茨凯维奇的《康拉德·瓦伦罗德》和《格拉伊娜》。后来我更喜欢斯沃瓦茨基。你知道为什么是斯沃瓦茨基吗?... 他是整个波兰的灵魂”。[15]:27。

1867年12月,阿波罗带着儿子来到奥地利控制的波兰地区,这里两年来一直享有相当大的内部自由和一定程度的自治。在利沃夫和几个较小的地方呆了一段时间后,1869年2月20日,他们搬到同样在奥属波兰的克拉科夫(1596年之前的波兰故都)。几个月后,1869年5月23日,阿波罗·科热日尼奥夫斯基去世,留下11岁的孤儿康拉德[15]:31–34 。和康拉德的母亲一样,阿波罗也患有严重的肺结核。

年轻的康拉德被安排由埃瓦的兄弟塔德乌斯·博布罗斯基照顾。康拉德身体不好,学习成绩也不尽如人意,给他舅舅带来不少麻烦,以及没完没了的支出。康拉德不是个好学生,尽管请了家庭教师,但仅在地理方面表现出色。[15]:43 由于他的病因明显来自神经系统,医生认为新鲜空气和身体锻炼有助于他强壮起来;他的舅舅希望用明确的职责和严谨的工作,让他学会纪律。由于他没有表现出什么学习的天赋,因此他必须学习一种贸易,他舅舅认为他合适做一个水手兼商人,他会把海事技能与商业活动结合起来。[15]:44–46 事实上,在1871年秋天,13岁的康拉德宣布他打算成为一名水手。他后来回忆说,他小时候读过利奥波德·麦克林托克的书(显然是法文译本),讲述他1857-59年狐狸号探险经历,寻找約翰·富蘭克林失踪的船只Erebus和Terror[note 10]。他还回忆说,曾读过美国人詹姆斯·菲尼莫尔·库珀和英国船长弗雷德里克·玛丽安特的书。[15]:41–42 他青春期的一位玩伴回忆说,康拉德表演纺纱,总是设定在海上,呈现得如此逼真,以至于听众认为行动就发生在他们眼前。

1873年8月,博布罗斯基把15岁的康拉德送到利沃夫一个由表兄弟开办的1863年一月起义留下的孤儿的男孩寄宿学校,互相交流使用法语。主人的女儿回忆道:

他和我们在一起只有十个月... 他非常聪明,但不喜欢学校常规。他常说...他计划成为一个伟大的作家...他不喜欢所有的限制。在家里,在学校,或在客厅里,都会不礼貌。他患有严重的头痛症[15]:43–44

。康拉德在这里仅一年多,1874年9月,由于不明原因,他舅舅将他从利沃夫的学校带走,带回到克拉科夫。

1874年10月13日,博布罗斯基将16岁的孩子送到法国马赛,计划从事海上职业。[15]:44–46 虽然康拉德没有完成中学学业,但他的会说流利的法语(带有正确的口音),一些拉丁语、德语和希腊语知识,可能精通历史知识,一些地理知识,而且可能对物理学感兴趣。他阅读很好,特别是波兰浪漫主义文学。他属于家族中必须在家庭庄园外谋生的第二代,在工作的知识阶层的环境中出生和长大,这个社会阶层在中欧和东欧开始发挥重要作用[15]:46–47。他吸收了他家乡的历史、文化和文学,最终能够形成独特的世界观,并对英国的文学做出独特的贡献[12]:1–5。他的童年在波兰长大,成年后在国外,这将产生康拉德最伟大的文学成就。[12]:246–47。同样是波兰移民的兹齐斯瓦夫·纳杰德,评价说:

一个人远离天然环境—家庭、朋友、社会团体、语言—即使是来自有意识的决定,也常常引起... 内在的紧张,因为它往往使人们对自己不太确定,更脆弱,更不确定他们的... 位置和...价值... 波兰贵族和...知识阶层是非常重视声誉和自我价值的社会阶层... ... 人们努力找到他们在别人眼里的...自我尊重的确认... ... 这种心理传统既是对雄心壮志的刺激,也是持续压力的来源,特别是如果被灌输了公共责任的思想的话。[15]:47

有人认为,当康拉德离开波兰时,他希望一次永远地与他的波兰过去断绝关系。[15]:97 纳杰德引用了康拉德在1883年8月14日写给家庭朋友斯特凡·布兹奇斯基的信,信是在康拉德离开波兰9年后写的:

... 我总是记得我离开克拉科夫时你说的话:记住—你说的“无论你在哪里航行,你都要航行到波兰!”我从未忘记,也永远不会忘记![15]:96

国籍

康拉德是俄国国籍,出生在原波兰立陶宛联邦的俄国占领区。1867年12月,在俄国政府允许下,他的父亲阿波罗将他带到原波兰立陶宛联邦的奥地利占领区,那里享有相当大的内部自由和一定程度的自治。父亲去世后,康拉德的舅舅博布罗斯基曾试图为他争取奥地利国籍——但无济于事,也许是因为康拉德没有得到俄国当局的许可,无法永久留在国外,也没有吊销俄国国籍。康拉德不能回到俄罗斯帝国境内的乌克兰,—那样他作为政治流亡者的儿子,将不得不服多年的兵役,并被骚扰[15]:41。

在1877年8月9日的信中,康拉德的舅舅博布罗斯基提出了两个重要议题:[note 11] 康拉德在国外入籍的可取性(相当于吊销了俄国国籍),以及康拉德加入英国商船的计划。你会说英语?...我从未希望你在法国入籍,主要是因为义务兵役... 然而,我想,你能在瑞士入籍..." 在下一封信中,博布罗斯基支持康拉德寻求美国或某个重要的南美洲共和国的公民身份的想法。[15]:57–58

最终康拉德在英国安家。1886年7月2日,他申请英国国籍,在1886年8月19日取得国籍。然而,虽然康拉德已经成为维多利亚女王的子民,但并没有吊销俄国国籍。为了吊销国籍,他不得不多次造访俄国驻伦敦大使馆,并礼貌地重申他的请求。他后来在小说《间谍》中,又回忆起在贝尔格雷夫广场的大使馆[15]:112。最后,在1889年4月2日,俄国内政部吊销了“写信的波兰人的儿子,英国商船船长”的俄国国籍[15]:132。

纪念

在波兰格丁尼亚的波罗的海海岸,有一座锚形的康拉德纪念碑,上面有他的波兰语名言:“Nic tak nie nęci, nie rozczarowuje i nie zniewala, jak życie na morzu”(“没有什么比海上生活更诱人,更令人神往”– 《吉姆爷》第2章第1段)。

在澳大利亚悉尼的環形碼頭(Circular Quay),有一块“作家步行”牌匾,纪念1879年至1892年之间,康拉德对澳大利亚的访问。牌匾上写道:“他的许多作品都反映了他对那个年轻大陆的喜爱。”[16]

1979年,旧金山渔人码头附近,哥伦布大道和海滩街的一个三角形小广场,命名为约瑟夫·康拉德广场(Joseph Conrad Square)。广场的命名时间恰好与弗朗西斯·科波拉根据《黑暗的心》改编的电影《现代启示录》上映时间吻合。

在第二次世界大战的后期,英国皇家海军巡洋舰HMS Danae号更名为康拉德号,作为波兰海军的一部分。

尽管康拉德在他的众多航程中,无疑受过许多苦,但是在他曾去过的好几个目的地,都有一些顶级酒店,运用精明的营销手段,声称曾是康拉德的住处。远东地区的酒店,仍然声称他是一位尊贵的客人,但是没有证据支持他们的主张:新加坡的萊佛士酒店 声称他住在那里,尽管他实际上是在附近的水手俱乐部住过的。他对曼谷的造访也保留在该市的集体记忆中,并记录在曼谷文华东方酒店的正式历史中,实际上,他从未在此住过,而是一直和行为不佳的客人威廉·萨默塞特·毛姆住在奥塔哥号船上,他在短篇小说中嘲笑了酒店,以报复酒店将他赶出。

在新加坡富麗敦酒店附近安装了一块纪念“約瑟夫·康拉德·科热日尼奥夫斯基”的牌匾。

据报道,康拉德还曾住过香港的半岛酒店—实际上,他从未去过这个港口。后来的文学崇拜者,尤其是格雷厄姆·格林,紧紧追随他的脚步,有时要求同一个房间,使得没有事实根据的神话长存下来。至今尚没有一处加勒比度假胜地标榜康拉德曾经光顾,但是 在1875年第一次搭乘“勃朗峰号”航行时,曾到达马提尼克的法兰西堡。

2013年4月,康拉德纪念碑在俄罗斯的沃洛格达揭幕,他和他的父母在1862–63年间流亡于此。该纪念碑于2016年6月被拆除,但未作解释[17]。

作品

注释

- Tim Middleton writes: "Referring to his dual Polish and English allegiances he once described himself as 'homo-duplex' (CL3: 89 [Joseph Conrad, Cambridge Collected Letters, vol. 3, p. 89])—the double man." Tim Middleton, Joseph Conrad, Routledge, 2006, p. xiv.

- Rudyard Kipling felt that "with a pen in his hand he was first amongst us" but that there was nothing English in Conrad's mentality: "When I am reading him, I always have the impression that I am reading an excellent translation of a foreign author." Cited in Jeffrey Meyers, Joseph Conrad: A Biography, p. 209. Cf. Zdzisław Najder's similar observation: "He was [...] an English writer who grew up in other linguistic and cultural environments. His work can be seen as located in the borderland of auto-translation." Zdzisław Najder, Joseph Conrad: A Life, 2007, p. ix.

- Conrad wrote: "In this world—as I have known it—we are made to suffer without the shadow of a reason, of a cause or of guilt.[...] There is no morality, no knowledge and no hope; there is only the consciousness of ourselves which drives us about a world that[...] is always but a vain and fleeting appearance." Jeffrey Meyers, Joseph Conrad: A Biography, 1991, p. 166.

- Conrad wrote of himself in 1902: "I am modern." Leo Robson, "The Mariner's Prayer", The New Yorker, 20 November 2017, p. 93.

- H.S. Zins writes: "Conrad made English literature more mature and reflective because he called attention to the sheer horror of political realities overlooked by English citizens and politicians. The case of Poland, his oppressed homeland, was one such issue. The colonial exploitation of Africans was another. His condemnation of imperialism and colonialism, combined with sympathy for its persecuted and suffering victims, was drawn from his Polish background, his own personal sufferings, and the experience of a persecuted people living under foreign occupation. Personal memories created in him a great sensitivity for human degradation and a sense of moral responsibility." H. S. Zins, "Joseph Conrad and British Critics of Colonialism", Pula, vol. 12, nos. 1 & 2, 1998, p. 63.

- Conrad's biographer Zdzisław Najder writes in a 2-page online article, "Jak się nazywał Joseph Conrad?" ("What Was Joseph Conrad's Name?"):

- "... When he was baptized at the age of two days, on 5 December 1857 in Berdyczów, no birth certificate was recorded because the baptism was only 'of water.' And during his official, documented baptism (in Żytomierz) five years later, he himself was absent, as he was in Warsaw, awaiting exile into Russia together with his parents.

- "Thus there is much occasion for confusion. This is attested by errors on tablets and monuments. But examination of documents—not many, but quite a sufficient number, survive—permits an entirely certain answer to the title question.

- "On 5 December 1857 the future writer was christened with three given names: Józef (in honor of his maternal grandfather), Teodor (in honor of his paternal grandfather) and Konrad (doubtless in honor of the hero of part III of Adam Mickiewicz's Dziady). These given names, in this order (they appear in no other order in any records), were given by Conrad himself in an extensive autobiographical letter to his friend Edward Garnett of 20 January 1900 (Polish text in Listy J. Conrada [Letters of J. Conrad], edited by Zdzisław Najder, Warsaw, 1968).

- "However, in the official birth certificate (a copy of which is found in the Jagiellonian University Library in Kraków, manuscript no. 6391), only one given name appears: Konrad. And that sole given name was used in their letters by his parents, Ewa, née Bobrowska, and Apollo Korzeniowski, as well as by all members of the family.

- "He himself signed himself with this single given name in letters to Poles. And this single given name, and the surname 'Korzeniowski,' figured in his passport and other official documents. For example, when 'Joseph Conrad' visited his native land after a long absence in 1914, just at the outbreak of World War I, the papers issued to him by the military authorities of the Imperial-Royal Austro-Hungarian Monarchy called him 'Konrad Korzeniowski.'"

- "Russia's defeat by Britain, France and Turkey [in the Crimean War] had once again raised hopes of Polish independence. Apollo celebrated his son's christening with a characteristic patriotic–religious poem: "To my son born in the 85th year of Muscovite oppression". It alluded to the partition of 1772, burdened the new-born [...] with overwhelming obligations, and urged him to sacrifice himself as Apollo would for the good of his country:

'Bless you, my little son:

Be a Pole! Though foes

May spread before you

A web of happiness

Renounce it all: love your poverty...

Baby, son, tell yourself

You are without land, without love,

Without country, without people,

While Poland – your Mother is in her grave

For only your Mother is dead – and yet

She is your faith, your palm of martyrdom...

This thought will make your courage grow,

Give Her and yourself immortality.'" Jeffrey Meyers, Joseph Conrad: a Biography, p. 10. - Zdzisław Najder, Conrad under Familial Eyes, Cambridge University Press, 1984, ISBN 0-521-25082-X.

- "X" is the Roman numeral for "Ten".

- It was still an age of exploration, in which Poles participated: Paweł Edmund Strzelecki mapped the Australian interior; the writer Sygurd Wiśniowski, having sailed twice around the world, described his experiences in Australia, Oceania and the United States; Jan Kubary, a veteran of the 1863 Uprising, explored the Pacific islands.

- Conrad's own letters to his uncle Tadeusz Bobrowski were destroyed during World War I. Zdzisław Najder, Joseph Conrad: A Life, 2007.

参考

- Brownstone, David M.; Franck, Irene M. . HarperCollins. 1994: 397. ISBN 978-0-062-70069-8.

- 约瑟夫·康拉德在《大英百科全书》在线版的页面 (英文)

- J. H. Stape, The New Cambridge Companion to Joseph Conrad. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014, p. 103–04.

- See J. H. Stape, The New Cambridge Companion to Joseph Conrad, p. 70, re Lord Jim, for example.

- Colm Tóibín writes: "[B]ecause he kept his doubleness intact, [Conrad] remains our contemporary, and perhaps also in the way he made sure that, in a time of crisis as much as in a time of calm, it was the quality of his irony that saved him." Colm Tóibín, "The Heart of Conrad" (review of Maya Jasanoff, The Dawn Watch: Joseph Conrad in a Global World, Penguin, 375 pp.), The New York Review of Books, vol. LXV, no. 3 (22 February 2018), p. 11. V. S. Naipaul writes: "Conrad's value to me is that he is someone who sixty to seventy years ago meditated on my world, a world I recognize today. I feel this about no other writer of the [20th] century." (Quoted in Colm Tóibín, "The Heart of Conrad", p. 8.) Maya Jasanoff, drawing analogies between events in Conrad's fictions and 21st-century world events, writes: "Conrad's pen was like a magic wand, conjuring the spirits of the future." (Quoted in Colm Tóibín, "The Heart of Conrad", p. 9.)

- Adam Hochschild makes the same point about Conrad's seeming prescience in his review of Maya Jasanoff's The Dawn Watch: Adam Hochschild, "Stranger in Strange Lands: Joseph Conrad lived in a far wider world than even the greatest of his contemporaries", Foreign Affairs, vol. 97, no. 2 (March / April 2018), pp. 150–55. Hochschild also notes (pp. 150–51): "It is startling... how seldom [in the late 19th century and the first decade of the 20th century, European imperialism in South America, Africa, and Asia] appear[ed] in the work of the era's European writers." Conrad was a notable exception.

- Zdzisław Najder, Joseph Conrad: A Life, Camden House, 2007, ISBN 978-1-57113-347-2, p. 352.

- Zdzisław Najder, Joseph Conrad: A Life, Camden House, 2007, ISBN 978-1-57113-347-2, p. 290.

- Zdzisław Najder, Joseph Conrad: A Life, Camden House, 2007, ISBN 978-1-57113-347-2, pp. 448–49.

- Henryk Zins (1982), Joseph Conrad and Africa, Kenya Literature Bureau, p. 12.

- John Stape, The Several Lives of Joseph Conrad, p 2.

- Stewart, J. I. M (1968) Joseph Conrad. Longman London; 1st Edition.

- Jeffrey Meyers, Joseph Conrad: a Biography, pp. 2–3.

- Jeffrey Meyers, Joseph Conrad: a Biography, pp. 10–11, 18.

- Najder, Z. . Camden House. 2007: 11–12. ISBN 978-1-57113-347-2.

- . [2009-01-01]. (原始内容存档于2009-02-07).

- . www.vologda.aif.ru. 2016-06-24.

外部連結

- The Joseph Conrad Society (U.K)

- biography at Joseph Conrad centre of Poland

- Conrad First: a digital archive of every newspaper and magazine in which the work of Joseph Conrad was first published

- Joseph Conrad的作品 - 古騰堡計劃