少年愛

少年愛(英語:)指古希臘社會中成年男子和少年間的男色關係。希臘語 παιδεραστία(Paiderastia)的前綴 παῖς意為「少年」,後綴 ἐραστής意為「情人」[1]。通常少年為關係中的被動方,年紀約莫在12歲到17歲之間[2]。在古希臘社會,少年愛是受到社會認可的習俗。在這種習俗裡,成年男子為「愛者」(erastês, lover),主動向青春期男孩求愛,設法讓這位男孩成為「愛人」(erômenos, beloved)。儘管此習俗通常涉及到性接觸,但該社會關係的主要目為指導男孩成為男人的公民品德教育,年長方會充當年輕一方在軍事、公民方面的教育者和導師[3]。

古希臘之外的社會或文化,也有近似於古希臘少年愛的男色關係而建立在成年男子和少年之間,曾出現於韓國、日本、中國和伊斯蘭等社會當中[2]。在日本,眾道(男色)存在於武士與侍從的主僕關係[4]。中國帝王或士人,寵愛清秀貌美(有時扮為女裝)的孌童,讚賞其姿色才藝[5]。新幾內亞尚比亞部落認為男孩可藉由吞食精液,而成為獲得男子氣概的男人。在那之後男人成為精液供給者,一直到和女性結婚之前[2]。

當代國家將未滿最低合法性交年齡視為尚未具備「性自主」的判斷能力[6],基於保護兒童和青少年免於性剝削,與未滿最低合法性交年齡的兒童和青少年發生性關係會受到政府處罰[7]。當代國家規定的最低合法性交年齡,大多訂定於14歲至16歲之間。

詞源

英語 pederasty 源於希臘語 παιδεραστία(paiderastia)。前綴 παῖς(boy)意為「男孩」,後綴 ἐραστής(lover)意為「情人」。而拉丁語 pæderasta 借自柏拉圖於《會飲篇》所用的古希臘文,此詞於文藝復興時期首次在英語中出現,寫作 pæderastie,表示成年男性與男孩的性關係。

特徵

儘管近代社會普遍以為少年愛等於男同性戀,或是少年愛屬於一種男同性戀現象,但這些說法都不完全正確。廣泛來看,少年愛涉及一些社會發展的因素,因為曾有一些文化從公眾層面就認同少年愛的存在。發展出制度化的純粹男性社群的文化(如早期的軍隊),都曾認同少年愛,或者將其視為體制的一部分[8]。

歷史

古希臘

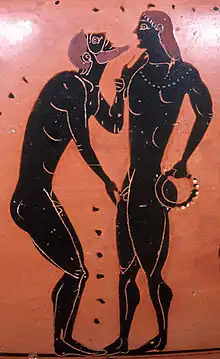

對於歷史上有關少年愛最早的描述,應該在古希臘。古希臘少年愛是古希臘時代被當時社會所公開承認的一種社會關係,通常是由一名成年男性和一名青少年組建而成[10] 。這種關係存在於古希臘古風時代和古典希臘時代[11] 。一些學者找到這種關係的儀式起源於克裡特島,這種儀式被認為是進入古希臘軍事生活和宙斯宗教的入門儀式[12]。根據現存的古希臘裸體男性雕塑,都刻意地把男性的性器官弄得比平常細,因為他們認為少年的性器比較美觀。

相關作品

世紀末少年愛讀本

《世紀末少年愛讀本》取材於清代道光年間陳森所著的《品花寶鑑》。書中以兩位讀書人和兩位男伶為主角,描寫了當時男伶以色娛人的生活。

少年愛的美學

《少年愛的美學》由日本正太作家創作的成人雜誌,內容為少年之間的性愛。包括(但不限於)女裝癖、獸人正太,以及有血緣的親兄弟間的情愫。

参考文献

- Oxford Dictionaries. . [2019-04-27]. (原始内容存档于2016-07-09).

- . Glbtq.com. [2015-11-22]. (原始内容存档于2014-10-08).

- 翁嘉聲. (PDF). 成大西洋史集刊. 1997, 7: 1–109 [2019-04-27]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2016-03-04).

- . [2019-04-27]. (原始内容存档于2019-08-04).

- 朱麗霞. . 江淮論壇. 2009. (原始内容存档于2016-03-14).

- 高級中等學校輔導教師參考手冊. . (原始内容存档于2015-12-22).

- Australian Institute of Family Studies. . [2019-04-27]. (原始内容存档于2019-08-02).

- 摘自《我類 页面存档备份,存于》,馬文·哈里斯(Marvin Harris,何睿思 )著,1994,時報文化出版,ISBN 9571312436,(繁體中文)

- J.D. Beazley, "Some Attic Vases in the Cyprus Museum", Proceedings of the British Academy 33 (1947); p.199; Dover, Greek Homosexuality, pp. 94-96.

- C.D.C. Reeve, Plato on Love: Lysis, Symposium, Phaedrus, Alcibiades with Selections from Republic and Laws (Hackett, 2006), p. xxi online 页面存档备份,存于; Martti Nissinen, Homoeroticism in the Biblical World: A Historical Perspective, translated by Kirsi Stjerna (Augsburg Fortress, 1998, 2004), p. 57 online 页面存档备份,存于; Nigel Blake et al., Education in an Age of Nihilism (Routledge, 2000), p. 183 online. 页面存档备份,存于

- Nissinen, Homoeroticism in the Biblical World, p. 57; William Armstrong Percy III, "Reconsiderations about Greek Homosexualities," in Same–Sex Desire and Love in Greco-Roman Antiquity and in the Classical Tradition of the West (Binghamton: Haworth, 2005), p. 17. Sexual variety, not excluding paiderastia, was characteristic of the Hellenistic era; see Peter Green, "Sex and Classical Literature," in Classical Bearings: Interpreting Ancient Culture and History (University of California Press, 1989, 1998), p. 146 online. 页面存档备份,存于

- Robert B. Koehl, "The Chieftain Cup and a Minoan Rite of Passage," Journal of Hellenic Studies 106 (1986) 99–110, with a survey of the relevant scholarship including that of Arthur Evans (p. 100) and others such as H. Jeanmaire and R.F. Willetts (pp. 104–105); Deborah Kamen, "The Life Cycle in Archaic Greece," in The Cambridge Companion to Archaic Greece (Cambridge University Press, 2007), pp. 91–92. Kenneth Dover, a pioneer in the study of Greek homosexuality, rejects the initiation theory of origin; see "Greek Homosexuality and Initiation," in Que(e)rying Religion: A Critical Anthology (Continuum, 1997), pp. 19–38. For Dover, it seems, the argument that Greek paiderastia as a social custom was related to rites of passage constitutes a denial of homosexuality as natural or innate; this may be to overstate or misrepresent what the initiatory theorists have said. The initiatory theory does not claim to account for the existence of homosexuality, but for formal paiderastia.

- Schalow, Paul Gordon. "Kukai and the Tradition of Male Love in Japanese Buddhism," in Cabezon, Jose Ignacio, Ed., Buddhism, Sexuality & Gender, State University of New York. p. 215.