英語史

英语起源于盎格鲁-弗里西亚方言,是在日耳曼人(主要来自今天的德国西北地区以及荷兰)入侵时被引入不列颠的。最初的古英语由多种方言组成,这也同时也反映了当时英格兰岛上的盎格鲁-撒克逊王国的起源具有多样性这一事实。这些方言其中的一种,晚期西撒克逊语最终成为了统一英语的语言。

英语语言在中世纪经历了巨大的变化。公元1000年的书面古英语在词汇和语法上与其他古日耳曼语(如古高地德语、古诺尔斯语)相似,现代人完全不能理解这个时期的古英语。现代人所认识的英语,很大程度上和公元1400年的书面中古英语相似。这种转变是由历史上两次入侵引起的。第一次是来自北日耳曼语支(也称斯堪的那维亚语支)的入侵,他们在公元八、九世纪征服并使部分不列颠岛成为他们的殖民地。第二次是十一世纪时来自诺曼人的入侵,他们讲的古诺曼语最终发展为英语的一种变体,称为盎格鲁-诺曼语。

与斯堪的那维亚半岛的密切来往引起了英语中大量的语法简化,同时也扩充了盎格鲁-弗里西亚语的词汇量(该语言处于英语核心地位)。然而,直到公元9世纪这些改变都还没有影响到英格兰的西南地区。也正是因为如此,该地区的古英语得以渐渐发展成为一门健全的语言。当书面英语最初崭露头角时,它是以离斯堪的那维亚殖民地的中心更近的伦敦地区的口头语言为基础发展而来的。与技术、文化相关的词汇大都从古诺曼语演化而来,尤其受到教堂、法庭和统治阶级的深远影响。后来的文艺复兴时期,和大多数其他正在发展中的欧洲语言(如德语、荷兰语、拉丁语、古希腊语)一样,取代了诺曼语和法语作为主要语言来源。至此,英语形成了一种词汇大量外借、不同词汇的来源迥异的混合形态。

原始英语

英语诞生于日耳曼人的语言,主要包括盎格鲁语,撒克逊语,弗里西语,朱特语。这其中还可能含有法兰克语,他们在欧洲民族大迁徙时期中,长达几个世纪的日耳曼人向欧洲西部扩张过程中,和说拉丁语的罗马帝国贸易来往,并有过交战。从拉丁语借来的词汇如 wine, cup 以及 bishop 等,他们在进入不列颠形成英语之前先进入了日耳曼人的词汇中。[1]

塔西佗于约公元前100年所著的《日耳曼尼亚志》,是研究日耳曼人(英语的祖先)在远古时代的文化信息的主要来源。日耳曼人和罗马文明有联系,和罗马的经济也有关联。日耳曼人曾在罗马军队服役,但保持政治上的独立。日耳曼军队由罗马指挥,在不列颠尼亚驻守。除了弗利西人,日耳曼人在英国的殖民地都如六世纪的英国宗教领袖吉尔达斯所述,在五世纪雇佣军到来之后大规模建立。大多数安格鲁人、撒克逊人和朱特人都是以日耳曼异教徒的身份进入不列颠的,他们独立于罗马的统治。

《盎格鲁-撒克逊编年史》叙述说,大约在449年,沃蒂根王(当时的不列颠王)曾邀请“安哥拉家族”(据信其领导人是日耳曼人兄弟 Hengist 和 Horsa),请他们来帮助驱逐侵略不列颠的皮克特人。作为回报,盎格鲁-撒克逊人接受了不列颠东南的一块土地。该编年史提到了一大批移居者最终建立七大王国的一段历史时期,史称七国时代。现代学者将 Hengist 和 Horsa 二人视为来自盎格鲁-撒克逊异教的“神话即历史论的论点的神”,并认为他们起源于原始印欧人。[2]

古英语(五世纪中叶到十一世纪中叶)

在盎格鲁-撒克逊入侵之后,日耳曼语言就取代了大不列颠某地区(现英格兰)上本土的布立吞语和拉丁语。凯尔特语则在苏格兰、威尔士、康沃尔等地保留下来。其中康沃尔人直到十九世纪都还在说凯尔特语。[3]拉丁语也在这些地区作为凯尔特教堂用语、受过高等教育的人使用的高尚语言得以保留。拉丁语后来还被凯尔特和罗马教堂的传教士重新引入英格兰,对英语语言产生很大影响。现在,人们现在所讲的古英语是长期以来多个殖民部落的方言融合而形成的。[4]即使是在当时,不同地方的古英语也有所不同。这一现象在现代英语的方言中有所残余。[4]现存最著名的古英语时期的著作是史诗《贝奥武甫》,其作者不详。

古英语与现代标准英语之间存在巨大差异。现今以英语为母语的人如果不把古英语当做另一门语言来学习的话,是无法看懂古英语的。尽管存在很多差异,但英语作为一门日耳曼语言,大约有一半的现代日常用词具有古英语词根。像 be, strong 以及 water 这些词,都源自古英语。很多非标准的方言,如苏格兰语、诺森伯兰语都保留了古英语的词汇和发音特点。[5]古英语的使用,一直延续到了十二或十三世纪。[6][7]

公元十、十一世纪,古英语受到了属于北日耳曼语支的古诺尔斯语的强烈影响。古诺尔斯语的使用者为诺尔斯人,他们曾侵略并定居在了英格兰的东北地区。盎格鲁-撒克逊人和北日耳曼人说的语言具有相关性,这些语言都来自不同的日耳曼语族分支。

古英语使用者的日耳曼语在与诺尔斯殖民者的密切来往中受到影响,这可能带来了古英语在形态上的简化,包括阴阳性的丢失、格的变化(代词除外)。英语大约从古诺尔斯语借用了两千个词条,比如:anger, bag, both, hit, law, leg, same, skill, sky, take 等等,还可能包括代词 they。[8]

由于公元六世纪晚期基督教的引入,超过400个拉丁词被借用引入英语,包括:priest, paper, school 等词,以及一些较少的希腊语词汇。[9]古英语时期正式结束是在1066年诺曼征服后,诺曼人开始大规模影响英语语言时。诺曼人讲的是一种叫古诺曼语的法语方言。用盎格鲁-撒克逊的叫法来形容盎格鲁和撒克逊语言、文化的融合是一种相对现代的做法。

中古英语(十一世纪晚期到十五世纪晚期)

诺曼征服后的几个世纪内,诺曼的国王以及高层贵族曾一度流行奥依语,该语言属法语的一种,称盎格鲁-诺曼语。该语言曾由许多在英格兰岛上的古诺曼人使用,在盎格鲁-诺曼时期,其使用范围甚至扩张到了不列颠群岛的其他地方,并受到北方奥依语方言的影响。商人和较低阶层的贵族曾经同时使用盎格鲁-诺曼语和英语,英语仍然被视为普通人使用的语言。中古英语同时受到盎格鲁-诺曼语和后来的盎格鲁-法语的影响。

即使是在诺曼-法语衰落之后,标准法语仍给人以正式、威望的感觉(这个时期内的大多欧洲人都这么认为),这对英语造成了巨大影响。这种影响在现代英语中可以找到。因此,今天人们普遍对源自法语的词感到非常正式,是由来已久的。举例来说,大多说现代英语的人认为“a cordial reception”(来源于拉丁语/法语) 较 "a hearty welcome"(相对德语“herzlich Willkommen”) 或者“complimentary”(来源于法语compliment)较“free”(相对德语frei)更为正式。另一个例子是,表示动物的词汇与代表他们的肉的词汇很少被分开创建。如代表牛(cow)和猪(pig)的肉的 beef 和 pork(来源于法语 bœuf 和 porc)。

英语也受到被其取代的凯尔特语言的影响,特别是布立吞语的影响。最明显的是“进行时”的引入,它是许多现代语言特征,但它是在英语中更早地、更充分地被发展的。[10]

《盎格鲁-撒克逊编年史》里记载到,1154年左右的文学作品都是用古诺曼语或拉丁语写的。古英语从诺曼语吸收了大量词汇,甚至有些词汇是本来古英语里就有的,但也都被吸收了进来,造成许多重复。诺曼语的影响是英语在受侵略后发生语言大转变的体现,正是这个转变过程产生了我们现在所称的中古英语。

英语文学在1200年后重新出现,受那时的政治氛围和盎格鲁-诺曼语言不断衰落的影响,英语变得愈加受尊重(即地位不再处于普通人的语言之列)。1258年的《牛津条约》(The Provision of Oxford)是自诺曼征服以来,首篇以英语出版的英国政府文稿。1362年爱德华三世成为首个用英语发表英国国会演讲的国王。到了十四世纪末,就连贵族阶层也开始使用英语。到这一时期,盎格鲁-诺曼语变成仅在小圈子内部使用的语言,后来就不再活跃了。

杰弗里·乔叟是中古英语时期最著名的作家,他所著的《坎特伯雷故事集》是他最有名的作品。虽然乔叟作品里的单词拼写与现代英语有所不同,但这些作品只需在一点点的辅助下即可读懂。

英语语言在中古英语时期经历了沧桑巨变,这种变化同时体现在语法和词汇上。古英语是一门严重受到其他语言影响的语言,非常纷繁复杂。但在中古英语时期,发生了词尾的全面精简。大量的名词和形容词的词尾被简化为 -e,原有的语法差异随之遗失。曾用于表示复数形式的词尾 -en 被大量简化为 -s,词的阴阳性被遗弃。中古英语从法语(也有诺曼语)借用了大约一万个词,特别是政府、交通、法律、军队、时尚和饮食方面的词汇。[11]

英语的拼写也同样在这一时期被诺曼语所影响。这一现象体现在:/θ/ 和 /ð/ 这两个音被拼写为 th,而不是古英语字母 þ(thorn)和 ð(eth)(这两个字母在诺曼语中不存在)。这些字母在由西挪威语从古英语借来的现代冰岛字母表中得到了保留。

近代英语(十五世纪晚期到十七世纪晚期)

英语语言在十五世纪时,拼写方面已经相对稳定了,但语音上经历了许多巨大变化。现代英语的语音的发展通常认为可追溯到开始于14世纪,大体完成于15世纪中期的元音大推移。英语语音后来又在政府所用的以伦敦口音为基础的方言,以及印刷行业的的影响下产生变形。在这种朝向标准化推进的过程中,英语内部产生了“口音”、“方言”等概念。[12]到威廉·莎士比亚时期(十六世纪中叶到十七世纪早期)为止[13],英语已经发展得与现代英语相似了。1604年,第一部英语字典诞生,名曰《Table Alphabeticall》。

随着文学作品不断增多,以及人们到处游历,英语吸收了大量的外来词,特别是文艺复兴后从拉丁语和希腊语吸收了大量的词汇。由于存在大量的不同语言的词汇,加之英语拼写非常多变,根据一个单词的写法读错读音是常有的现象,但古代形式在一些地区的方言中仍有残余,尤见于英格兰岛的西南地区。在这个时期,英语从意大利语、德语、依地语借入了许多词汇。英国人对于美国风俗的种种接受和反抗即从这一时期开始。[14]

现代英语(十七世纪晚期至今)

《约翰逊字典》是由英国大文豪塞缪尔·约翰逊编撰的一本全功能英语字典。这本在1755年首次出版的权威字典,在很大程度上规范化了英语词汇的拼写和用法。同时,Robert Lowth, Lindley Murray, Joseph Priestley 等尝试规范英语的人,编写了语法教科书。

近代英语和晚期现代英语在词汇上有本质的不同。晚期现代英语的词汇量大得多,这些词大量产生于工业革命和亟需新词的技术,以及受到英语在国际上发展的影响。大英帝国全盛时期曾统治了地球四分之一的面积,英语也由此吸收了大量的外语。英国英语和美国英语这两大英语分支,被全世界4亿人所使用。英国英语的“皇室口音”最有声望,而通俗美国口音的影响力更大。全世界说英语的人数加起来可能超过10亿。[15]

语法变化

英语语言曾经有过一套与拉丁语、现代德语以及冰岛语类似的复杂的变格系统。古英语词汇的主格、宾格、与格、属格的词形都不相同。对于强变格形容词,以及某些代词,还存在一套工具格(后来和与格的变化形式完全一致)。另外,双数和现在的单复数变化十分不同。[16] 变格系统在中古英语时期被大量简化,代词的宾格和与格合并为“间接格”。间接格后来也替代了位于介词后的属格。现代英语的名词不再具有除属格以外的变格。

英语代词的演变

英语中 who 和 whom,he 和 him,she 和 her 等词,都是古代宾格和与格融合的结果,介词后面的属格也是这种融合产生的。这种融合的形式被称作“间接格”,英语术语为 oblique case 或 object (objective) case。这是由于该词格变化用于动词的动作对象(Object),也用于指出某词是介词所指的对象。原有的靠词格变化传递信息的方式,在现代英语中通常由介词和语序的变化所代替。古英语、现代德语以及冰岛语中,这些词格变化都还存在。

虽然“宾格”和“与格”这两个传统术语仍为某些语法学家所用,但现在来看这些只是形式而已,他们在现代英语中已经失去了真正的“格”的意义。也就是说,whom 这个词也许能表现出宾格或与格的意义(还可能是工具格或介词格),但它只是一种单一的形态,因此属于单格。这与主格 who 和属格 whose 的关系形成对比。许多语法学家使用更为直观的术语,如“subjective”,“objective”,“possessive”来表达代词的主格、间接格和属格。

现代英语名词只在属格上和主格有所不同,也有语言学家指出,这根本就不算词格变化,只是一种附着词素而已。

疑问代词

| 格 | 古英语 | 中古英语 | 现代英语 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 阳性/阴性 (人称) | 主格 | hwā | who | who |

| 宾格 | hwone / hwæne | whom | who / whom1 | |

| 与格 | hwām / hwǣm | |||

| 工具格 | ||||

| 属格 | hwæs | whos | whose | |

| 中性 (物称) | 主格 | hwæt | what | what |

| 宾格 | hwæt | what / whom | ||

| 与格 | hwām / hwǣm | |||

| 工具格 | hwȳ / hwon | why | why | |

| 属格 | hwæs | whos | whose2 |

1 - 某些方言中,who 在正式英语中必须用 whom,尽管方言差异必须考虑在内

2 - 通常被 of what 代替

第一人称代词

| 格 | 古英语 | 中古英语 | 现代英语 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 单数 | 主格 | iċ | I / ich / ik | I |

| 宾格 | mē / meċ | me | me | |

| 与格 | mē | |||

| 属格 | mīn | min / mi | my, mine | |

| 复数 | 主格 | wē | we | we |

| 宾格 | ūs / ūsiċ | us | us | |

| 与格 | ūs | |||

| 属格 | ūser / ūre | ure / our | our, ours |

(古英语也有一套单独的双数系统,比如用 wit 表示 we two 等等,这种形式在演变过程中完全消失了。)

第二人称代词

| 格 | 古英语 | 中古英语 | 现代英语 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 单数 | 主格 | þū | þu / thou | thou (you) |

| 宾格 | þē / þeċ | þé / thee | thee (you) | |

| 与格 | þē | |||

| 属格 | þīn | þi / þīn / þīne / thy /thin / thine | thy, thine (your) | |

| 复数 | 主格 | ġē | ye / ȝe / you | you |

| 宾格 | ēow / ēowiċ | you, ya | ||

| 与格 | ēow | |||

| 属格 | ēower | your | your, yours | |

注意 ye 和 you 的区别仍然存在,至少有些时候存在,比如在近代英语 “Ye shall know the truth and the truth shall make you free” 就有所体现(参见《钦定版圣经》)。

| 古英语 | 中古英语 | 现代英语 | ||||||||||

| 单数 | 复数 | 单数 | 复数 | 单数 | 复数 | |||||||

| 格 | 正式 | 非正式 | 正式 | 非正式 | 正式 | 非正式 | 正式 | 非正式 | 正式 | 非正式 | 正式 | 非正式 |

| 主格 | þū | ġē | you | thou | you | ye | you | |||||

| 宾格 | þē / þeċ | ēow / ēowiċ | thee | you | ||||||||

| 与格 | þē | ēow | ||||||||||

| 属格 | þīn | ēower | your, yours | thy, thine | your, yours | your, yours | ||||||

第三人称代词

| 格 | 古英语 | 中古英语 | 现代英语 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 阳性单数 | 主格 | hē | he | he |

| 宾格 | hine | him | him | |

| 与格 | him | |||

| 属格 | his | his | his | |

| 阴性单数 | 主格 | hēo | heo / sche / ho / he / ȝho | she |

| 宾格 | hīe | hire / hure / her / heore | her | |

| 与格 | hire | |||

| 属格 | hire | hir / hire / heore / her / here | her, hers | |

| 中性单数 | 主格 | hit | hit / it | it |

| 宾格 | hit | hit / it / him | ||

| 与格 | him | |||

| 属格 | his | his / its | its | |

| 复数 | 主格 | hīe | he / hi / ho / hie / þai / þei | they |

| 宾格 | hīe | hem / ham / heom / þaim / þem / þam | them | |

| 与格 | him | |||

| 属格 | hira | here / heore / hore / þair / þar | their, theirs |

(they 的现代形式的起源通常被认为是古诺尔斯语的 þæir, þæim, þæira。这两套不同的词根共存了一段时间,但现在他们余存的共同点就只有 'em 这个缩略形式了。)

历代英语样例

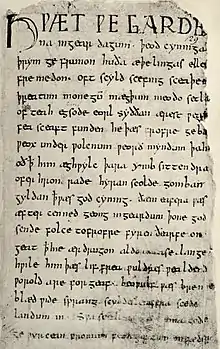

古英语

节选自《贝奥武甫》第 1 到 11 行, 约公元900年

Hwæt! Wē Gār-Dena in geārdagum, þēodcyninga þrym gefrūnon, hū ðā æþelingas ellen fremedon. Oft Scyld Scēfing sceaþena þrēatum, monegum mǣgþum, meodosetla oftēah, egsode eorlas. Syððan ǣrest wearð fēasceaft funden, hē þæs frōfre gebād, wēox under wolcnum, weorðmyndum þāh, oðþæt him ǣghwylc þāra ymbsittendra ofer hronrāde hȳran scolde, gomban gyldan. Þæt wæs gōd cyning!

以下是 Francis Gummere 对上文的翻译,以供参考:

Lo, praise of the prowess of people-kings

of spear-armed Danes, in days long sped,

we have heard, and what honor the athelings won!

Oft Scyld the Scefing from squadroned foes,

from many a tribe, the mead-bench tore,

awing the earls. Since erst he lay

friendless, a foundling, fate repaid him:

for he waxed under welkin, in wealth he throve,

till before him the folk, both far and near,

who house by the whale-path, heard his mandate,

gave him gifts: a good king he!

节选自《The Voyages of Ohthere》《Wulfstan》。全文可在维基文库中的 The Voyages of Ohthere and Wulfstan 找到。

Ōhthere sǣde his hlāforde, Ælfrēde cyninge, ðæt hē ealra Norðmonna norþmest būde. Hē cwæð þæt hē būde on þǣm lande norþweardum wiþ þā Westsǣ. Hē sǣde þēah þæt þæt land sīe swīþe lang norþ þonan; ac hit is eal wēste, būton on fēawum stōwum styccemǣlum wīciað Finnas, on huntoðe on wintra, ond on sumera on fiscaþe be þǣre sǣ. Hē sǣde þæt hē æt sumum cirre wolde fandian hū longe þæt land norþryhte lǣge, oþþe hwæðer ǣnig mon be norðan þǣm wēstenne būde. Þā fōr hē norþryhte be þǣm lande: lēt him ealne weg þæt wēste land on ðæt stēorbord, ond þā wīdsǣ on ðæt bæcbord þrīe dagas. Þā wæs hē swā feor norþ swā þā hwælhuntan firrest faraþ. Þā fōr hē þā giet norþryhte swā feor swā hē meahte on þǣm ōþrum þrīm dagum gesiglau. Þā bēag þæt land, þǣr ēastryhte, oþþe sēo sǣ in on ðæt lond, hē nysse hwæðer, būton hē wisse ðæt hē ðǣr bād westanwindes ond hwōn norþan, ond siglde ðā ēast be lande swā swā hē meahte on fēower dagum gesiglan. Þā sceolde hē ðǣr bīdan ryhtnorþanwindes, for ðǣm þæt land bēag þǣr sūþryhte, oþþe sēo sǣ in on ðæt land, hē nysse hwæþer. Þā siglde hē þonan sūðryhte be lande swā swā hē meahte on fīf dagum gesiglan. Ðā læg þǣr ān micel ēa ūp on þæt land. Ðā cirdon hīe ūp in on ðā ēa for þǣm hīe ne dorston forþ bī þǣre ēa siglan for unfriþe; for þǣm ðæt land wæs eall gebūn on ōþre healfe þǣre ēas. Ne mētte hē ǣr nān gebūn land, siþþan hē from his āgnum hām fōr; ac him wæs ealne weg wēste land on þæt stēorbord, būtan fiscerum ond fugelerum ond huntum, ond þæt wǣron eall Finnas; ond him wæs āwīdsǣ on þæt bæcbord. Þā Boermas heafdon sīþe wel gebūd hira land: ac hīe ne dorston þǣr on cuman. Ac þāra Terfinna land wæs eal wēste, būton ðǣr huntan gewīcodon, oþþe fisceras, oþþe fugeleras.

译文:

Ohthere said to his lord, King Alfred, that he of all Norsemen lived north-most. He quoth that he lived in the land northward along the North Sea. He said though that the land was very long from there, but it is all wasteland, except that in a few places here and there Finns [i.e. Sami] encamp, hunting in winter and in summer fishing by the sea. He said that at some time he wanted to find out how long the land lay northward or whether any man lived north of the wasteland. Then he traveled north by the land. All the way he kept the waste land on his starboard and the wide sea on his port three days. Then he was as far north as whale hunters furthest travel. Then he traveled still north as far as he might sail in another three days. Then the land bowed east (or the sea into the land — he did not know which). But he knew that he waited there for west winds (and somewhat north), and sailed east by the land so as he might sail in four days. Then he had to wait for due-north winds, because the land bowed south (or the sea into the land — he did not know which). Then he sailed from there south by the land so as he might sail in five days. Then a large river lay there up into the land. Then they turned up into the river, because they dared not sail forth past the river for hostility, because the land was all settled on the other side of the river. He had not encountered earlier any settled land since he travelled from his own home, but all the way waste land was on his starboard (except fishers, fowlers and hunters, who were all Finns). And the wide sea was always on his port. The Bjarmians have cultivated their land very well, but they did not dare go in there. But the Terfinn’s land was all waste except where hunters encamped, or fishers or fowlers.[17]

Whan that Aprille with his shoures soote

The droghte of March hath perced to the roote

And bathed every veyne in swich licour,

Of which vertu engendred is the flour;

Whan Zephirus eek with his sweete breeth

Inspired hath in every holt and heeth

The tendre croppes, and the yonge sonne

Hath in the Ram his halfe cours yronne,

And smale foweles maken melodye,

That slepen al the nyght with open yë

(So priketh hem Nature in hir corages);

Than longen folk to goon on pilgrimages近代英语

节选自约翰·弥尔顿所写的《失乐园》,1667年版

Of man's first disobedience, and the fruit

Of that forbidden tree, whose mortal taste

Brought death into the world, and all our woe,

With loss of Eden, till one greater Man

Restore us, and regain the blissful seat,

Sing, Heavenly Muse, that on the secret top

Of Oreb, or of Sinai, didst inspire

That shepherd, who first taught the chosen seed,

In the beginning how the Heavens and Earth

Rose out of chaos: or if Sion hill

Delight thee more, and Siloa's brook that flowed

Fast by the oracle of God, I thence

Invoke thy aid to my adventurous song,

That with no middle Flight intends to soar

Above the Aonian mount, whyle it pursues

Things unattempted yet in prose or rhyme.现代英语

The evening arrived: the boys took their places; the master in his cook's uniform stationed himself at the copper; his pauper assistants ranged themselves behind him; the gruel was served out, and a long grace was said over the short commons. The gruel disappeared, the boys whispered each other and winked at Oliver, while his next neighbours nudged him. Child as he was, he was desperate with hunger and reckless with misery. He rose from the table, and advancing, basin and spoon in hand, to the master, said, somewhat alarmed at his own temerity—

"Please, sir, I want some more."

The master was a fat, healthy man, but he turned very pale. He gazed in stupefied astonishment on the small rebel for some seconds, and then clung for support to the copper. The assistants were paralysed with wonder, and the boys with fear.

"What!" said the master at length, in a faint voice.

"Please, sir," replied Oliver, "I want some more."

The master aimed a blow at Oliver's head with the ladle, pinioned him in his arms, and shrieked aloud for the beadle.

参见

注释

- Baugh, Albert and Cable, Thomas. 2002. The History of the English Language. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice Hall. pp. 79-81.

- Examples include Simek (2007:59—60) and Mallory (2005:135).

- Crystal, David. 2004. The Stories of English. London: Penguin. pp. 24-26.

- Shore, Thomas William, 1nd, London: 3, 393, 1906

- . Bl.uk. 2007-03-12 [2010-06-19].

- . Uni-kassel.de. [2010-06-19].

- The Oxford history of English lexicography, Volume 1 By Anthony Paul Cowie

- Baugh, Albert and Cable, Thomas. 2002. The History of the English Language. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice Hall. pp. 92-105.

- Baugh, Albert and Cable, Thomas. 2002. The History of the English Language. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice Hall. pp. 91-92.

- Filppula, Markku, Juhani Klemola und Heli Pitkänen (eds.). 2002. The Celtic Roots of English. Joensuu: University of Joensuu, Faculty of Humanities.

- Baugh, Albert and Cable, Thomas. 2002. The History of the English Language. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice Hall. pp. 158-178.

- Crystal, David. 2004. The Stories of English. London: Penguin. pp. 341-343.

- See Fausto Cercignani, Shakespeare's Works and Elizabethan Pronunciation, Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1981.

- Algeo, John. 2010. The Origins and Development of the English Language. Boston, MA: Wadsworth. pp. 140-141.

- Algeo, John. 2010. The Origins and Development of the English Language. Boston, MA: Wadsworth. pp. 182-187.

- Peter S. Baker. . The Electronic Introduction to Old English. Oxford: Blackwell. 2003. (原始内容存档于2015-09-11).

- Original translation for this article: In this close translation readers should be able to see the correlation with the original.

引用

- Cercignani, Fausto, Shakespeare's Works and Elizabethan Pronunciation, Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1981.

- Mallory, J. P (2005). In Search of the Indo-Europeans. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-27616-1

- Simek, Rudolf (2007) translated by Angela Hall. Dictionary of Northern Mythology.D.S. Brewer. ISBN 0859915131

外部链接